If you’ve lived in Florida for a while, you know how wild the housing market can get. Booms, busts, and bubbles, it’s all nothing new. But back in 1928, Venice nearly vanished. The place almost turned into a ghost town, and for a while, it was. What saved it? A school of all things.

Let’s rewind a bit. Venice started out with the odd nickname Horse and Chaise, thanks to a tree that looked like a carriage. Fishermen used it as a landmark. In the 1870s, Robert Rickford Roberts officially founded the city, and that’s why you’ll still see his name on Roberts Bay.

Frank Higel arrived in 1883, bringing his wife and six sons along. He kicked off a citrus business, and by 1888, he’d set up a post office. He named it Venice, thinking the area’s canals reminded him of his childhood in Italy.

Pretty soon, the place filled up with pioneers, cattle ranchers and farmers. But it wasn’t until trains rolled in that things really picked up. And you have Bertha Honore Palmer to thank for that. She pushed to get railroad tracks laid all the way down here.

The 1920s brought a real estate frenzy. Bertha Palmer sold 112 acres to Dr. Fred Albee, an orthopedic surgeon with big dreams for Venice. He wanted to build a medical center and turn the city into something special, so he brought in John Nolan to design it. Nolan went for a European- Mediterranean style that still gives Venice its charm.

But Dr. Albee didn’t hang on to his investment for long. He sold to the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers (BLE), which had big plans to develop the area, market the property, and build a city right on the Gulf of Mexico. Five-acre plots farther inland would serve for agriculture. In 1926, Dr. Nolen finished the city plan.

Everyone was chasing quick money back then, flipping land and hoping to cash in. It looked like a sure thing until 1928. Suddenly, the money dried up. The BLE packed up and left.

That’s when Venice turned into a ghost town. The population dropped to just 300 people, and this was a year before the Great Depression hit. Things looked grim.

Then, in 1932, the BLE leased out the San Marco Hotel and the Venice Hotel to the Kentucky Military Institute (KMI) for use as classrooms and dorms. The town welcomed the cadets with open arms; thousands showed up at the train station to greet them. The money the school brought in saved Venice, and overnight, the cadets doubled the town’s population.

KMI needed a place to escape the harsh Kentucky winters, so the deal worked out for everyone. For almost 40 years, cadets, teachers, and some parents would roll into town by train right after New Year’s and stay until Easter. But in 1971, with the Vietnam War stirring up controversy, the school closed for good.

Over the years, plenty of interesting folks have called Venice home. The Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus even set up their winter headquarters here in 1960, putting on shows for 31 years.

These days, the circus, the railroads, and the military school are all gone. But Venice? It’s thriving, more beautiful than ever.

The old San Marco Hotel is now a retail building, and inside, you’ll find a display dedicated to the Kentucky Military Institute’s history.

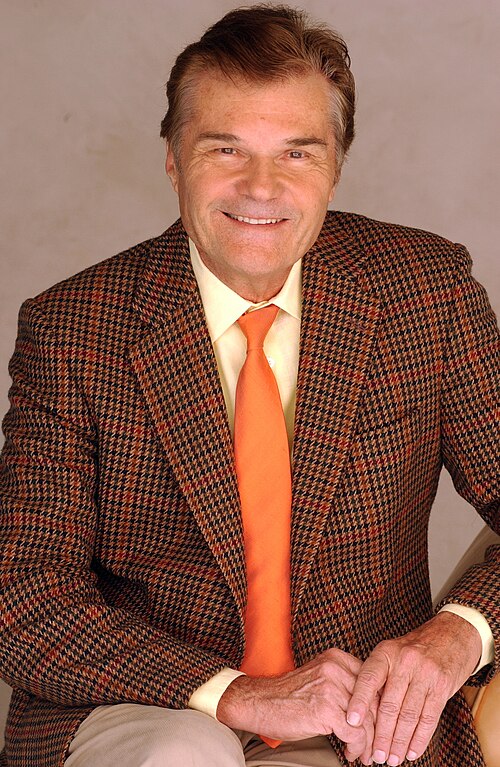

And if you’re curious about famous KMI alumni, here’s a little trivia: Fred Willard of Modern Family fame once walked these streets, and so did Jim Backus, better known as Thurston Howell III from Gilligan’s Island. Not bad for a town that refused to disappear.